|

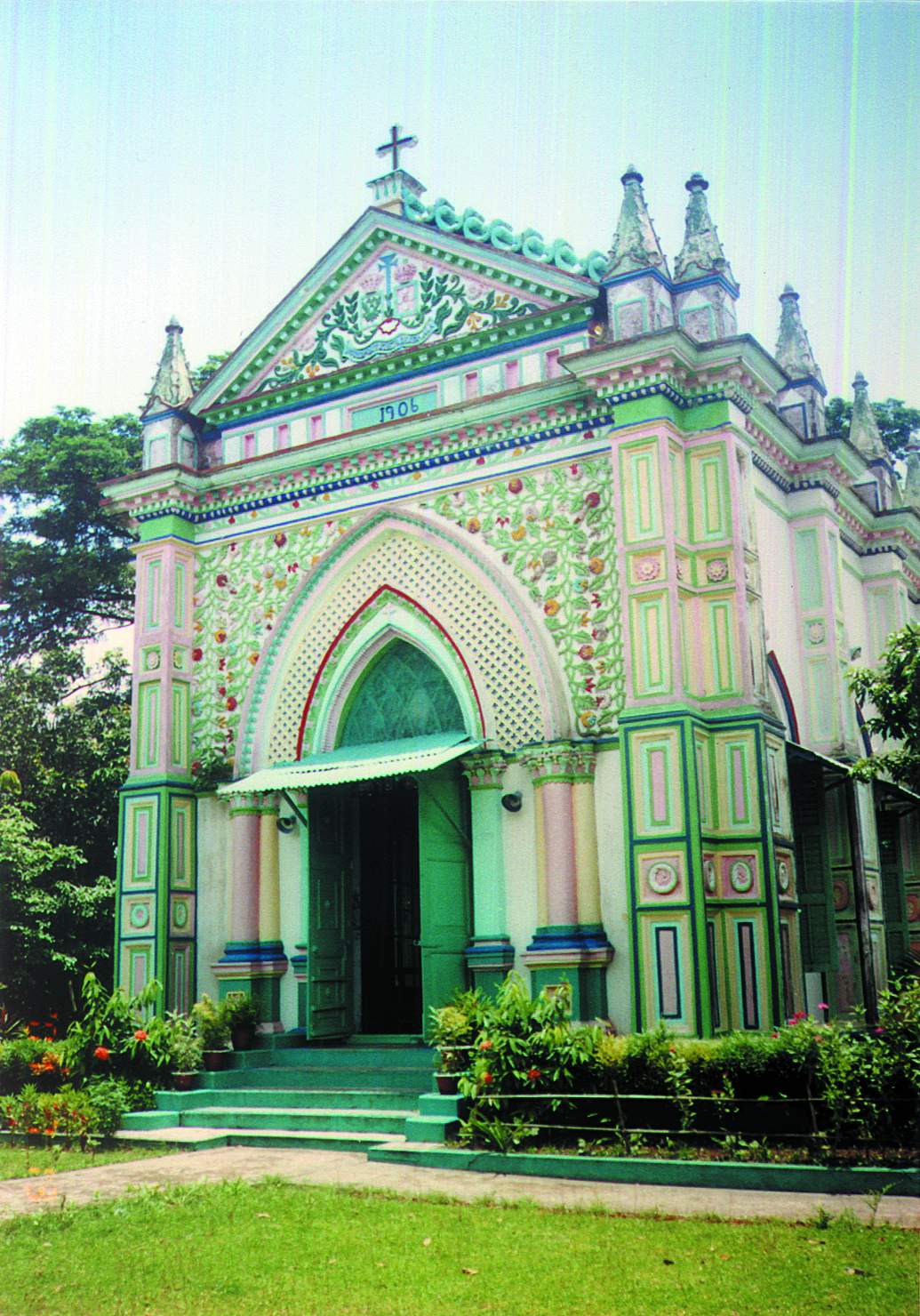

Anthoney in Nagari

Tomb of Christina Parish, who had donated the land of Panjura Church

Life History

Franciscan Thaumaturgist, born at

Lisbon, 1195; died at Vercelli, 13 June, 1231. He received in baptism the name of Ferdinand.

Later writers of the

fifteenth century asserted that his father was Martin Bouillon, descendant of the renowned Godfrey de Bouillon, commander

of the First Crusade, and his mother, Theresa Tavejra, descendant of Froila I, fourth king of Asturia. Unfortunately, however,

his genealogy is uncertain; all that we know of his parents is that they were noble, powerful, and God-fearing people, and

at the time of Ferdinand's birth were both still young, and living near the Cathedral of Lisbon.

Having been educated

in the Cathedral school, Ferdinand, at the age of fifteen, joined the Canons Regular of St. Augustine, in the convent of St.

Vincent, just outside the city walls (1210). Two years later to avoid being distracted by relatives and friends, who frequently

came to visit him, he betook himself with permission of his superior to the Convent of Santa Croce in Cóimbra (1212), where

he remained for eight years, occupying his time mainly with study and prayer. Gifted with an excellent understanding and a

prodigious memory, he soon gathered from the Sacred Scriptures and the writings of the Holy Fathers a treasure of theological

knowledge.

In the year 1220, having seen conveyed into the Church of Santa Croce the bodies of the first Franciscan

martyrs, who had suffered death at Morocco, 16 January of the same year, he too was inflamed with the desire of martyrdom,

and resolved to become a Friar Minor, that he might preach the Faith to the Saracens and suffer for Christ's sake. Having

confided his intention to some of the brethren of the convent of Olivares (near Cóimbra), who came to beg alms at the Abbey

of the Canons Regular, he received from their hands the Franciscan habit in the same Convent of Santa Croce. Thus Ferdinand

left the Canons Regular of St. Augustine to join the Order of Friars Minor, taking at the same time the new name of Anthony,

a name which later on the Convent of Olivares also adopted.

A short time after his entry into the order, Anthony started

for Morocco, but, stricken down by a severe illness, which affected him the entire winter, he was compelled to sail for Portugal

the following spring, 1221. His ship, however, was overtaken by a violent storm and driven upon the coast of Sicily, where

Anthony then remained for some time, till he had regained his health. Having heard meanwhile from the brethren of Messina

that a general chapter was to be held at Assisi, 30 May, he journeyed thither, arriving in time to take part in it. The chapter

over, Anthony remained entirely unnoticed.

"He said not a word of his studies", writes his earliest biographer, "nor

of the services he had performed; his only desire was to follow Jesus Christ and Him crucified". Accordingly, he applied to

Father Graziano, Provincial of Cóimbra, for a place where he could live in solitude and penance, and enter more fully into

the spirit and discipline of Franciscan life. Father Graziano, being just at that time in need of a priest for the hermitage

of Montepaolo (near Forli), sent him thither, that he might celebrate Mass for the lay-brethren.

While Anthony lived

retired at Montepaolo it happened, one day, that a number of Franciscan and Dominican friars were sent together to Forli for

ordination. Anthony was also present, but simply as companion of the Provincial. When the time for ordination had arrived,

it was found that no one had been appointed to preach. The superior turned first to the Dominicans, and asked that one of

their number should address a few words to the assembled brethren; but everyone declined, saying he was not prepared. In their

emergency they then chose Anthony, whom they thought only able to read the Missal and Breviary, and commanded him to speak

whatever the spirit of God might put into his mouth. Anthony, compelled by obedience, spoke at first slowly and timidly, but

soon enkindled with fervour, he began to explain the most hidden sense of Holy Scripture with such profound erudition and

sublime doctrine that all were struck with astonishment. With that moment began Anthony's public career.

St. Francis,

informed of his learning, directed him by the following letter to teach theology to the brethren:

To Brother Anthony,

my bishop (i.e. teacher of sacred sciences), Brother Francis sends his greetings. It is my pleasure that thou teach theology

to the brethren, provided, however, that as the Rule prescribes, the spirit of prayer and devotion may not be extinguished.

Farewell. (1224)

Before undertaking the instruction, Anthony went for some time to Vercelli, to confer with the famous

Abbot, Thomas Gallo; thence he taught successively in Bologna and Montpellier in 1224, and later at Toulouse. Nothing whatever

is left of his instruction; the primitive documents, as well as the legendary ones, maintain complete silence on this point.

Nevertheless, by studying his works, we can form for ourselves a sufficient idea of the character of his doctrine; a doctrine,

namely, which, leaving aside all arid speculation, prefers an entirely seraphic character, corresponding to the spirit and

ideal of St. Francis.

It was as an orator, however, rather than as professor, that Anthony reaped his richest harvest.

He possessed in an eminent degree all the good qualities that characterize an eloquent preacher: a loud and clear voice, a

winning countenance, wonderful memory, and profound learning, to which were added from on high the spirit of prophecy and

an extraordinary gift of miracles. With the zeal of an apostle he undertook to reform the morality of his time by combating

in an especial manner the vices of luxury, avarice, and tyranny. The fruit of his sermons was, therefore, as admirable as

his eloquence itself. No less fervent was he in the extinction of heresy, notably that of the Cathares and the Patarines,

which infested the centre and north of Italy, and probably also that of the Albigenses in the south of France, though we have

no authorized documents to that effect. Among the many miracles St. Anthony wrought in the conversion of heretics, the three

most noted recorded by his biographers are the following:

The first is that of a horse, which, kept fasting for

three days, refused the oats placed before him, till he had knelt down and adored the Blessed Sacrament, which St. Anthony

held in his hands. Legendary narratives of the fourteenth century say this miracle took place at Toulouse, at Wadding, at

Bruges; the real place, however, was Rimini.

The second most important miracle is that of the poisoned food offered him

by some Italian heretics, which he rendered innoxious by the sign of the cross.

The third miracle worthy of mention is

that of the famous sermon to the fishes on the bank of the river Brenta in the neighbourhood of Padua; not at Padua, as is

generally supposed.

The zeal with which St. Anthony fought against heresy, and the great and numerous conversions he made

rendered him worthy of the glorious title of Malleus hereticorum (Hammer of the Heretics). Though his preaching was always

seasoned with the salt of discretion, nevertheless he spoke openly to all, to the rich as to the poor, to the people as well

as those in authority. In a synod at Bourges in the presence of many prelates, he reproved the Archbishop, Simon de Sully,

so severely, that he induced him to sincere amendment.

After having been Guardian at Le-Puy (1224), we find Anthony

in the year 1226, Custos Provincial in the province of Limousin. The most authentic miracles of that period are the following:

Preaching one night on Holy Thursday in the Church of St. Pierre du Queriox at Limoges, he remembered he had to

sing a Lesson of the Divine Office. Interrupting suddenly his discourse, he appeared at the same moment among the friars in

choir to sing his Lesson, after which he continued his sermon.

Another day preaching in the square des creux des Arenes

at Limoges, he miraculously preserved his audience from the rain.

At St. Junien during the sermon, he predicted that by

an artifice of the devil the pulpit would break down, but that all should remain safe and sound. And so it occurred; for while

he was preaching, the pulpit was overthrown, but no one hurt; not even the saint himself.

In a monastery of Benedictines,

where he had fallen ill, he delivered by means of his tunic one of the monks from great temptations.

Likewise, by breathing

on the face of a novice (whom he had himself received into the order), he confirmed him in his vocation.

At Brive, where

he had founded a convent, he preserved from the rain the maid-servant of a benefactress who was bringing some vegetables to

the brethren for their meagre repast.

This is all that is historically certain of the sojourn of St. Anthony in Limousin.

Regarding the celebrated apparition of the Infant Jesus to our saint, French writers maintain it took place in the

province of Limousin at the Castle of Chateauneuf-la-Forêt, between Limoges and Eymoutiers, whereas the Italian hagiographers

fix the place at Camposanpiero, near Padua. The existing documents, however, do not decide the question. We have more certainty

regarding the apparition of St. Francis to St. Anthony at the Provincial Chapter of Arles, whilst the latter was preaching

about the mysteries of the Cross.

After the death of St. Francis, 3 October, 1226, Anthony returned to Italy. His

way led him through La Provence on which occasion he wrought the following miracle: Fatigued by the journey, he and his companion

entered the house of a poor woman, who placed bread and wine before them. She had forgotten, however, to shut off the tap

of the wine-barrel, and to add to this misfortune, the Saint's companion broke his glass. Anthony began to pray, and suddenly

the glass was made whole, and the barrel filled anew with wine.

Shortly after his return to Italy, Anthony was elected

Minister Provincial of Emilia. But in order to devote more time to preaching, he resigned this office at the General Chapter

of Assisi, 30 May, l230, and retired to the Convent of Padua, which he had himself founded. The last Lent he preached was

that of 1231; the crowd of people which came from all parts to hear him, frequently numbered 30,000 and more. His last sermons

were principally directed against hatred and enmity, and his efforts were crowned with wonderful success. Permanent reconciliations

were effected, peace and concord re-established, liberty given to debtors and other prisoners, restitutions made, and enormous

scandals repaired; in fact, the priests of Padua were no longer sufficient for the number of penitents, and many of these

declared they had been warned by celestial visions, and sent to St. Anthony, to be guided by his counsel. Others after his

death said that he appeared to them in their slumbers, admonishing them to go to confession.

At Padua also took place

the famous miracle of the amputated foot, which Franciscan writers attribute to St. Anthony. A young man, Leonardo by name,

in a fit of anger kicked his own mother. Repentant, he confessed his fault to St. Anthony who said to him: "The foot of him

who kicks his mother deserves to be cut off." Leonardo ran home and cut off his foot. Learning of this, St. Anthony took the

amputated member of the unfortunate youth and miraculously rejoined it.

Through the exertions of St. Anthony, the

Municipality of Padua, 15 March, 1231, passed a law in favour of debtors who could not pay their debts. A copy of this law

is still preserved in the museum of Padua. From this, as well as the following occurrence, the civil and religious importance

of the Saint's influence in the thirteenth century is easily understood. In 1230, while war raged in Lombardy, St. Anthony

betook himself to Verona to solicit from the ferocious Ezzelino the liberty of the Guelph prisoners. An apocryphal legend

relates that the tyrant humbled himself before the Saint and granted his request. This is not the case, but what does it matter,

even if he failed in his attempt; he nevertheless jeopardized his own life for the sake of those oppressed by tyranny, and

thereby showed his love and sympathy for the people. Invited to preach at the funeral of a usurer, he took for his text the

words of the Gospel: "Where thy treasure is, there also is thy heart." In the course of the sermon he said: "That rich man

is dead and buried in hell; but go to his treasures and there you will find his heart." The relatives and friends of the deceased,

led by curiosity, followed this injunction, and found the heart, still warm, among the coins. Thus the triumph of St. Anthony's

missionary career manifests itself not only in his holiness and his numerous miracles, but also in the popularity and subject

matter of his sermons, since he had to fight against the three most obstinate vices of luxury, avarice and tyranny.

At

the end of Lent, 1231, Anthony retired to Camposanpiero, in the neighbourhood of Padua, where, after a short time he was taken

with a severe illness. Transferred to Vercelli, and strengthened by the apparition of Our Lord, he died at the age of thirty-six

years, on 13 June, 1231. He had lived fifteen years with his parents, ten years as a Canon Regular of St. Augustine, and eleven

years in the Order of Friars Minor.

Immediately after his death he appeared at Vercelli to the Abbot, Thomas Gallo,

and his death was also announced to the citizens of Padua by a troop of children, crying: "The holy Father is dead; St. Anthony

is dead!" Gregory IX, firmly persuaded of his sanctity by the numerous miracles he had wrought, inscribed him within a year

of his death (Pentecost, 30 May, 1232), in the calendar of saints of the Cathedral of Spoleto. In the Bull of canonization

he declared he had personally known the saint, and we know that the same pontiff, having heard one of his sermons at Rome,

and astonished at his profound knowledge of the Holy Scriptures called him: "Ark of the Covenant". That this title is well-founded

is also shown by his several works: "Expositio in Psalmos", written at Montpellier, 1224; the "Sermones de tempore", and the

"Sermones de Sanctis", written at Padua, 1229-30.

The name of Anthony became celebrated throughout the world, and

with it the name of Padua. The inhabitants of that city erected to his memory a magnificent temple, whither his precious relics

were transferred in 1263, in presence of St. Bonaventure, Minister General at the time. When the vault in which for thirty

years his sacred body had reposed was opened, the flesh was found reduced to dust but the tongue uninjured, fresh, and of

a lively red colour. St. Bonaventure, beholding this wonder, took the tongue affectionately in his hands and kissed it, exclaiming:

"O Blessed Tongue that always praised the Lord, and made others bless Him, now it is evident what great merit thou hast before

God."

The fame of St. Anthony's miracles has never diminished, and even at the present day he is acknowledged as the

greatest thaumaturgist of the times. He is especially invoked for the recovery of things lost, as is also expressed in the

celebrated responsory of Friar Julian of Spires:

Si quaeris miracula . . .

. . . resque perditas.

Indeed

his very popularity has to a certain extent obscured his personality. If we may believe the conclusions of recent critics,

some of the Saint's biographers, in order to meet the ever-increasing demand for the marvellous displayed by his devout clients,

and comparatively oblivious of the historical features of his life, have devoted themselves to the task of handing down to

posterity the posthumous miracles wrought by his intercession. We need not be surprised, therefore, to find accounts of his

miracles that may seem to the modern mind trivial or incredible occupying so large a space in the earlier biographies of St.

Anthony. It may be true that some of the miracles attributed to St. Anthony are legendary, but others come to us on such high

authority that it is impossible either to eliminate them or explain them away a priori without doing violence to the facts

of history.

NICOLAUS DAL-GAL

Transcribed by Frank O'Leary

The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume I

Copyright

© 1907 by Robert Appleton Company

Online Edition Copyright © 1999 by Kevin Knight

Nihil Obstat, March 1, 1907. Remy

Lafort, S.T.D., Censor

Imprimatur. +John Cardinal Farley, Archbishop of New York

Why St. Anthony Holds the Child Jesus

Most of us are familiar with the popular image of St. Anthony holding the infant Jesus. But do we know why he is portrayed

this way?

By Jack Wintz, O.F.M.

Looking for the Deeper Meanings

Anthony's Franciscan

Ties

An Eloquent Preacher Holding Up the Word

We, Too, Can Carry Christ

St. Anthony and the Lily

The child Jesus is a good symbol of what we are celebrating this yearthe 2,000th anniversary of

the Incarnation and birth of Jesus. Its the perfect year to explore why the image is so closely associated with St. Anthony

of Padua.

Next to Mary of Nazareth, the saint most often seen in artwork holding the child Jesus in his arms is

St. Anthony of Padua. If there is anything Ive learned from visiting churches and Catholic missions throughout the world,

it is that the image of Anthony and the child Jesus is a favorite around the globe. It can be found wherever Catholic missionaries

have carried the Good News, even in the most remote regions of the world.

Since I grew up in a Franciscan parish

(in southern Indiana) and was then educated in the Franciscan seminary system, I was very familiar with that image. How could

I avoid it? And yet for most of my life, I seldom asked others or myself: Why is St. Anthony presented that way?

I

have consistently found the image of Anthony with the child Jesus quite friendly and likable. Even as I encountered artists

who smiled at the image in patronizing ways and dismissed it as too sweet and sentimental, this did not keep me from finding

the image appealing.

For a good part of my life, I did not look for a deeper meaning in this familiar image. Nor

did I ask why the image caught the popular fancy of almost every culture around the world.

Looking for the Deeper

Meanings

In recent years, however, Ive taken a whole different tack. Ive concluded that this popular image has developed

in the Franciscan tradition and in the Catholic consciousness for some profound reason. For me, it conveys something vitally

important in the Franciscan and Catholic spirit.

Exploring this image is something like exploring a vivid dream

weve had during the night. We wake up the next morning and wonder, Now what was that all about? We assume that this dream,

emerging from our inner depths, may hold an important meaning for our lives. So, too, the images that rise from the inner

life of the Church may well hold profound meanings for us.

It is interesting to note that, although Anthony has

been frequently portrayed in art since his death in 1231, images of him with the Christ child did not become popular until

the 17th century.

Before exploring the image of Anthony and the Christ child, however, we should look at one of

the popular stories explaining the origin of the custom. A good number of Franciscan historians, I believe, would advise us

to approach the story as legend rather than as solid historical fact.

According to one version of the legendand

there are manythere was a Count Tiso who had a castle about 11 miles from Padua, Italy. On the grounds of the castle the count

had provided a chapel and a hermitage for the friars.

Anthony often went there toward the end of his life and spent

time praying in one of the hermit cells. One night, his little cell suddenly filled up with light. Jesus appeared to Anthony

in the form of a tiny child. Passing by the hermitage, the count saw the light shining from the room and St. Anthony holding

and communicating with the infant.

The count fell to his knees upon seeing this wondrous sight. And when the vision

ended, Anthony saw the count kneeling at the open door. Anthony begged Count Tiso not to reveal what he had seen until after

his death.

Whether this story be legend or fact, the image of Anthony with the child Jesus has important truths

to teach us.

Anthony's Franciscan Ties

First of all, we notice that Anthony is wearing a Franciscan habit.

Seeing him as a true son of St. Francis and a part of the Franciscan tradition is very important.

It is a historical

fact that Anthony joined the Order of Friars Minor while Francis was still alive. We know that Anthony attended the Franciscan

chapter of Pentecost, 1221, at which Francis was also present. Although more than 2,000 friars came to that famous gathering

near Assisi, its hard to believe that Anthonyfamous for finding lost objects for everyone else!would not have been resourceful

enough to find a way to see and hear the much-loved and illustrious founder of the Franciscan brotherhood, or perhaps even

meet him. Less than three years later, Anthony received a personal letter from Francis graciously granting him permission

to teach theology to the friars.

What Im getting at is that Anthony, being a committed member of Francis Order,

would have known well the spirit, teachings, values and dramatic actions of Francis. Like the other friars, he would have

surely heard about Francis famous celebration of Christmas near Greccio, Italy, in 1223.

On that occasion, St. Francis

had people come to Midnight Mass in a cave where there was an ox and an ass and a manger filled with straw. And the story

went around that the Christ child appeared in the straw and Francis held the child in his arms. How interesting! The story

of the baby Jesus appearing to Anthony is a kind of copycat story amazingly similar to that of St. Francis.

Even

more important is the attitude or theology behind the story. Francis, we know, was tremendously impressed by the poverty and

littleness of Goda God who left behind his divinity and chose to become a vulnerable child. In Gods entering the human race

as a little baby on Christmas Day, Francis saw a God of unbelievable generosity, a God who held nothing back from human beings,

a God of total self-giving, humility and poverty.

The poverty of God made a strong impression on St. Francis, according

to evidence in his Rule. In the sixth chapter, he instructs his followers that they should serve the Lord in Poverty...because

the Lord made himself poor for us in this world.

Anthony would have read this rule often. More than this, he would

have taken to heart the larger spiritual vision of St. Francis, which extended beyond his fascination with the feast of Christmas.

St. Francis also saw Gods poverty and vulnerability and self-giving love in Jesus suffering and death, so much so that he

often broke into tears at the sight of a cross. He saw Gods poverty in the Eucharist, as well, where under the common forms

of bread and wine Jesus humbly hands his whole self over to those he loves.

To see St. Anthony holding the infant

Jesus in his arms, therefore, is to see a true follower of St. Francis. For did not Francis also embrace that same image of

Gods vulnerability and humble love?

An Eloquent Preacher Holding Up the Word

Another meaningful way to

interpret the presence of the Christ child in the arms of St. Anthony is to realize that Anthony was a great preacher of the

gospela brilliant communicator of the Incarnate Word. In his sermons, Anthony emphasized the mystery of the Incarnation.

In 1946, Pope Pius XII officially declared Anthony a Doctor of the Universal Church, with the designation Doctor

of the Gospel. Clearly, Anthony had taught Scripture with great power and effectiveness.

This leads us to view the

images of Anthony holding the infant in a whole new light: Through his Scripture-based preaching, the real, historical Anthony

was holding and communicating to the world the Incarnate Word of God. Very often the infant in Anthonys arms is portrayed

as standing on the holy Bible. Can there be a more obvious symbol and clue that the Christ child in Anthonys arms represents

the very embodiment of the Word of God? Often, the child stands on the Bibles open pages as if rising out of the printed word

itself.

In San Antonio, Texas, there is a large and lovely statue of St. Anthony of Padua, the patron saint of the

city. The statue was a gift of Portugal (Anthonys birthplace) to San Antonio. It stands in a public park along the San Antonio

River in the heart of the city. The Christ child in Anthonys arms stands on the Bible and his arms are extended in the shape

of the cross as if embracing the whole worldas if Anthony is saying: I hold up to all, as Savior of the world, this humble

God of self-emptying love!

We, Too, Can Carry Christ

The image of Anthony holding the divine infant is

a symbol and model for each of us. The image inspires us to go through life clinging to the wonderful mystery of the humble,

self-emptying Christ, who accompanies us as a servant of our humanity and of the worlds healing.

This is the image

of Christ that St. Paul sketches for us in his Letter to the Philippians. Paul urges that we take on the attitude of Christ

Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave, being born in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of deatheven death

on a cross (2:6-8).

This passage from Philippians is a key building block of Franciscan spirituality. And if the

infant in Anthonys arms were to speak, Philippians 2:6-8 would be his first message and self-description.

Just as

Jesus death on a cross reveals Gods total self-giving love for us, so also does his Incarnation (symbolized in the Christ

child). The eminent Scripture scholar, the late Father Raymond Brown, has affirmed that the divine self-giving revealed in

Jesus Incarnation is comparable to Gods supreme act of love...embodied in Jesus self-giving on the cross. Brown adds, Indeed

some theologians have so appreciated the intensity of love in the Incarnation that they have wondered whether that alone might

not have saved the world even if Jesus was never crucified.

This is the kind of love that radiates from the Christ

child so often pictured in St. Anthonys arms. Would it not be a good idea for all of us to go through life carrying an imaginary

God-child in our armsand holding him up to the world? The child, however, is not really imaginary or fictitious. Two thousand

years ago, thanks to the Virgin Marys Yes, the Son of God left behind his divine condition and came to dwell among us as a

human child. Our faith tells us that he does accompany us each day like a humble servantlike a vulnerable child.

Like

St. Anthony, we do well lovingly to carry this image with us on our life journey.

Getting to Know Him:

A Closer Look at St. Anthony of Padua

by Carol Ann Morrow

from A Retreat With St. Anthony

of Padua: Finding Our Way

Listen to the author read this excerpt!

Carol Ann Morrow's book, A Retreat with

St. Anthony of Padua: Finding Our Way, offers fresh insights into the beloved friar who followed in the footsteps of St. Francis.

The following is the introduction to the book, written in the voice of the "spiritual director" for this "Retreat

With" book, St. Anthony of Padua.

You want to know who I am? It is the work of a lifetime. I believe the way of

holiness is to learn one's path and follow itover land and sea if necessary. And I have been so very lost! I have been lost

at sea, I have been lost on solid ground.

But now I am here and I am willing to share my losses and my discoveries with

you. I am Friar Anthony. I follow the way of Brother Francis of Assisi. They call him the Little Poor Man. Perhaps some call

me the Big Poor Man. I am larger by far than my spiritual father but I, too, want to be a simple, traveling preacher. And

that is why you've come, isn't it, to hear me preach from my heart what Francis has taught me of the gospel.

I want to

know you as well. I want to be at home with you, to discover what moves you, touches you, what brings you here. But first

you want to know who it is who is searching for answers with you during this retreat. So I'll tell you a little of my story.

I was not always called Anthony. I was born Fernando Bulhom in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1195 or perhaps a little earlierit

matters little. Our family home was very near to the cathedral church, which did matter. My parents were fairly well-off.

When I was about fifteen, I already knew I wanted to live where the Gospels were honored and I became an Augustinian at St.

Vincent's Outside the Walls. Being outside the walls didn't isolate St. Vincent's from the capital city's bustle, though,

so I later asked to be transferred to Santa Cruz in Coimbra.

I thought Coimbra might be more tranquil, but when I arrived

I still felt like I was outsideseparated from something essential to my soul's journey. Coimbra was the intellectual center

of Portugal, though, and I feasted on the volumes in the monastery library, learning much.

Then our monastery was given

the honor to house the remains of the first Franciscan martyrs. It was a political decision to give Santa Cruz these precious

relics, but it had spiritual repercussions for me. Perhaps some of you have visited the twentieth-century gravesite of Martin

Luther King, Jr., in Atlanta, the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., or another place made holy by the presence of

someone you love. Do you remember the vitality of your spiritual connection to those people, those events? That is how I felt

when I saw those martyrs' bones. That is what I wanted: I wanted to risk everything to speak the words of Jesus.

But Santa

Cruz Monastery was home to men who had grown comfortable, even careless with the gospel. The bones of the first five Franciscan

martyrs would dry and crumble there, and be gathered into little reliquaries. I wanted to live in Ezekiel's valley where the

bones of the martyrs could rise up and prophesy anew. When the Franciscans, new to Portugal in 1220, came to our door begging,

I begged for the privilege of joining them. I wanted to take my own young bones as soon as possible to preach to the Saracens.

How could the Moroccan people who had so influenced my homeland, who knew so much of beauty and adventure, how could they

not know Jesus as I did? My own risk seemed so small to buy so great a treasure for a whole people.

I may seem impetuous

to you. Sometimes I seem so to myself. But, once again, I left a safe place for the open road, to find my way. The friars

were new to Portugal, new to the Church, new to me. But the gospel was their compass and I knew they would lead me in a direction

good for my soul.

In Morocco, I preached not a single word, humbled by a body martyred only by illness, not by scimitars.

When I felt well enough to sail back to Portugal, storms blew our ship all the way to Sicily insteadfar, far from my homeland

but near to the home of my spiritual father. All of us Franciscans were itinerants of a sort, so I've been on the road ever

since.

My work was to help ordinary people puzzled by preachers who had either chosen or stumbled into heresies. I was

to reason with, inspire, bless and lead them. Today I might be compared to a politician on the campaign trailonly my campaign

was simply to use my knowledge of many things to help people make spiritual connections.

I lived in Europe's Middle Ages,

when the style of preaching and teaching, the worldview and the social climate were very different from what you've experienced.

You may find that my wordsas writtenseem florid and heavy. But when I spoke, I lit a fire in people's hearts. How else could

I have gathered audiences so large that they couldn't fit in the largest church but had to sit in fields and meadows?

So

I've told you the circuitous path I took from Lisbon, Portugal, to Padua, Italy, by way of Morocco and Sicily. Now I'd like

you to know what that world was like.

Placing Our Director in Context

I lived in what is now called the High Middle

Agesa time of social and religious upheaval, chaos and new beginnings.

My native country is Portugal, recognized as an

independent nation by the pope in 1179. I was born in Lisbon during the reign of Sancho I, Portugal's second king. Legend

says that Lisbon was founded by the Greek hero Odysseus. Sometimes I feel that I followed his star of travel and adventure

in my own life. Before my time, my homeland had often been under the control of the African Moors. King Sancho extended Portugal's

borders with the help of the Knights Templar and other crusaders. The king encouraged religious life, founding monasteries

such as the one in which I came to live.

The Canons Regular of St. Augustine differed from monks in that we worked as

pastors, connecting to the world outside our monastery through preaching and works of charity.

While I was at Santa Cruz

Monastery in Coimbra, the people of Castile (now part of Spain) definitively ended the power of the Almohads (a Muslim power).

Coimbra was then the nation's capital and our Portuguese queen consort, sister of the victorious Castilian leader, came to

Santa Cruz to express her thanks in public prayer.

Although our Holy Father Francis of Assisi is, I am sure, better known

to most people now, Emperor Frederick II and Pope Innocent III were the more powerful in my lifetime. It was Innocent who

approved Francis' way of life. He believed in his authority over political rulers and exercised it with some success. Within

the Church, he called the Fourth Lateran Council, which struggled with heresy and legislated the reception of the sacraments,

two areas which later touched my life and mission.

Innocent also called for a crusade against the Albigensian heresy and

the Fourth Crusade to the Holy Land. The Crusaders recaptured Jerusalem in 1229, though it was lost again some years after

my death.

Italy, with which I am most often identified, was my home only for little over a decade. At the time I lived

there, Rome was the capital of the Papal States and what you now call Italy was linked mostly by geography. Venice, so near

my Padua, was the link between Europe and the Orient and the launching point for many crusaders.

Italy held many walled

and fortified cities, little princes and small tyrants. Padua is said to be the oldest city in the country. Its university

is the country's oldest. Universities were new in my lifetime, not only in Portugal and Italy, but in all the known world.

You should also know that the times in which I lived saw a transition from an agrarian, barter economy to a merchant,

cash economy. This movement to the city with its trades, crafts and guilds was not a smooth one. The numbers of the poor increased

drastically. Many people had never owned land. Those who did sometimes had to sell it for cash. When they were out of cash,

they had to borrow. If crops were bad or they became ill, the interest mounted, and they lost any hope of regaining their

foothold. They became permanently poor, many of them living on the edge of forests, foraging, begging, eking out a precarious

existence.

Religion was the warp and woof weaving the days and nights of medieval life together and influencing the life

of the nation. Religion was the first and most public motive of the Crusades, although I wouldn't have you think they were

only about faith. This was the world in which Francis of Assisi founded the Order of Friars Minor and, later, the Poor Clares

and the lay Third Order, whose members were not to fight in these many skirmishes between cities. This was the world into

which I came, more educated than the man I elected to follow, more cosmopolitan, one might say, but just as eager to bring

Jesus to those who had yet to know of him.

This is the world in which I spent just thirty-six yearsnot so short a life

by the standards of the time. It is the setting in which I found all that I wish to share with you now.

Devotion to

St. Anthony of Padua

by Norman Perry, O.F.M.

EARLY EVERYWHERE

St.

Anthony is asked to intercede with God for the return of things lost or stolen. Those who feel very familiar with him may

pray, "Tony, Tony, turn around. Something's lost and must be found."

The reason for invoking St. Anthony's

help in finding lost or stolen things is traced back to an incident in his own life. As the story goes, Anthony had a book

of psalms that was very important to him. Besides the value of any book before the invention of printing, the psalter had

the notes and comments he had made to use in teaching students in his Franciscan Order.

A novice who had already

grown tired of living religious life decided to depart the community. Besides going AWOL he also took Anthony's psalter! Upon

realizing his psalter was missing, Anthony prayed it would be found or returned to him. And after his prayer the thieving

novice was moved to return the psalter to Anthony and return to the Order which accepted him back. Legend has embroidered

this story a bit. It has the novice stopped in his flight by a horrible devil brandishing an ax and threatening to trample

him underfoot if he did not immediately return the book. Obviously a devil would hardly command anyone to do something good.

But the core of the story would seem to be true. And the stolen book is said to be preserved in the Franciscan friary in Bologna.

In any event, shortly after his death people began praying through Anthony to find or recover lost and stolen articles.

And the Responsory of St. Anthony composed by his contemporary, Julian of Spires, O.F.M., proclaims, "The sea obeys and

fetters break/And lifeless limbs thou dost restore/While treasures lost are found again/When young or old thine aid implore."

St. Anthony and the Child Jesus

St. Anthony has been pictured by artists and sculptors in all

kinds of ways. He is depicted with a book in his hands, with a lily or torch. He has been painted preaching to fish, holding

a monstrance with the Blessed Sacrament in front of a mule or preaching in the public square or from a nut tree.

But

since the 17th century we most often find the saint shown with the child Jesus in his arm or even with the child standing

on a book the saint holds. A story about St. Anthony related in the complete edition of Butler's Lives of the Saints (edited,

revised and supplemented by Herbert Anthony Thurston, S.J., and Donald Attwater) projects back into the past a visit of Anthony

to the Lord of Chatenauneuf. Anthony was praying far into the night when suddenly the room was filled with light more brilliant

than the sun. Jesus then appeared to St. Anthony under the form of a little child. Chatenauneuf, attracted by the brilliant

light that filled his house, was drawn to witness the vision but promised to tell no one of it until after St. Anthony's death.

Some may see a similarity and connection between this story and the story in the life of St. Francis when he reenacted

at Greccio the story of Jesus, and the Christ Child became alive in his arms. There are other accounts of appearances of the

child Jesus to Francis and some companions.

These stories link Anthony with Francis in a sense of wonder and awe

concerning the mystery of Christ's incarnation. They speak of a fascination with the humility and vulnerability of Christ

who emptied himself to become one like us in all things except sin. For Anthony, like Francis, poverty was a way of imitating

Jesus who was born in a stable and would have no place to lay his head.

Patron of Sailors, Travelers

and

Fishermen

In Portugal, Italy, France and Spain, St. Anthony is the patron saint of sailors and fishermen.

According to some biographers his statue is sometimes placed in a shrine on the ship's mast. And the sailors sometimes scold

him if he doesn't respond quickly enough to their prayers.

Not only those who travel the seas but also other travelers

and vacationers pray that they may be kept safe because of Anthony's intercession. Several stories and legends may account

for associating the saint with travelers and sailors.

First, there is the very real fact of Anthony's own travels

in preaching the gospel, particularly his journey and mission to preach the gospel in Morocco, a mission cut short by severe

illness. But after his recovery and return to Europe he was a man always on the go, heralding the Good News.

There

is also a story of two Franciscan sisters who wished to make a pilgrimage to a shrine of our Lady but did not know the way.

A young man is supposed to have volunteered to guide them. Upon their return from the pilgrimage one of the sisters announced

that it was her patron saint, Anthony, who had guided them.

Still another story says that in 1647 Father Erastius

Villani of Padua was returning by ship to Italy from Amsterdam. The ship with its crew and passengers was caught in a violent

storm. All seemed doomed. Father Erastius encouraged everyone to pray to St. Anthony. Then he threw some pieces of cloth that

had touched a relic of St. Anthony into the heaving seas. At once, the storm ended, the winds stopped and the sea became calm.

Teacher, Preacher, Doctor

of the Scriptures

Among the Franciscans themselves and in the

liturgy of his feast, St. Anthony is celebrated as a teacher and preacher extraordinaire. He was the first teacher in the

Franciscan Order, given the special approval and blessing of St. Francis to instruct his brother Franciscans. His effectiveness

as a preacher calling people back to the faith resulted in the title "Hammer of Heretics." Just as important were

his peacemaking and calls for justice.

In canonizing Anthony in 1232, Pope Gregory IX spoke of him as the "Ark

of the Testament" and the "Repository of Holy Scripture." That explains why St. Anthony is frequently pictured

with a burning light or a book of the Scriptures in his hands. In 1946 Pope Pius XII officially declared Anthony a Doctor

of the Universal Church. It is in Anthony's love of the word of God and his prayerful efforts to understand and apply it to

the situations of everyday life that the Church especially wants us to imitate St. Anthony. While noting in the prayer of

his feast Anthony's effectiveness as an intercessor, the Church wants us to learn from Anthony, the teacher, the meaning of

true wisdom and what it means to become like Jesus, who humbled and emptied himself for our sakes and went about doing good.

Franciscan Father Norman Perry (1929-1999) served as editor-in-chief of St. Anthony Messenger magazine for 18 years.

He was the anonymous friar behind the publication's popular "Wise Man" column for the 32 years he served on the

magazine staff. This excerpt is from the book Saint Anthony of Padua: The Story of His Life and Popular Devotions, which was

published in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of St. Anthony Messenger.

|